Share

|

As fires like the devastating Camp Fire occur nationwide, water quality crises have become part of the aftermath. In recent years wildfires have claimed cities, communities and millions of acres of land. According to the National Interagency Fire Center, 10 million acres burned in 2017, 8.8 million in 2018, and already 171,000 acres have been lost in 2019. Wildfires are not just a threat to aboveground structures, but underground infrastructure, too. On multiple occasions, wildfires have melted plastic piping and contaminated underground potable water networks with carcinogens and other dangerous chemicals.

When wildfires melt pipes made of plastic, it releases volatile chemicals such as benzene, a carcinogenic hydrocarbon associated with crude oil that’s strictly regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency. Even if a building survives a wildfire, breaches in the system miles away can still contaminate its water.

Melted plastic piping components can also create entry points for ash, super heated air and debris, permitting chemical contamination in quantities far above health standards. Since underground piping networks are vast and complex, identifying contamination sources is its own challenge and requires extensive testing. If an area has several plastic piping installations, the problem can quickly grow as undamaged plastic pipes absorb chemicals present in the water.

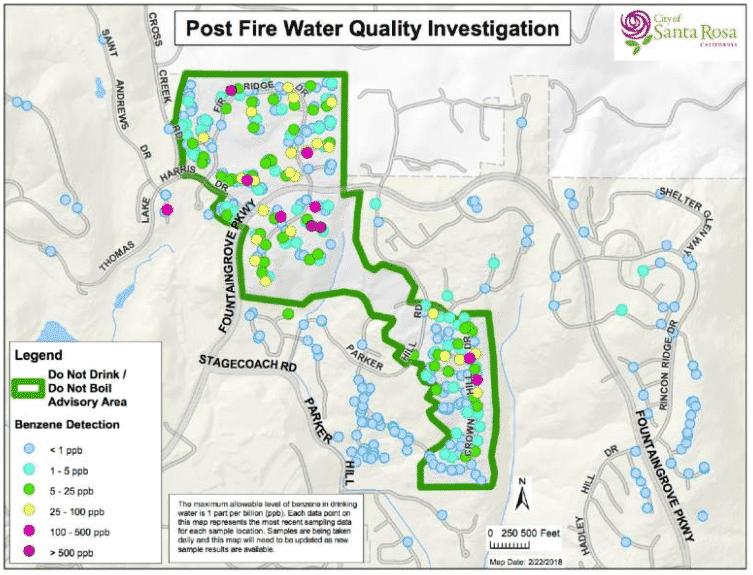

The city of Santa Rosa, California provides an example of how serious this problem can become. The 2017 Tubbs Fire burned 36,807 acres,

destroyed 5,636 structures and extensively damaged several parts of the city, including Fountaingrove (below). After the fire, community officials discovered the water system was contaminated with benzene.

Following an investigation, the city’s water department concluded “…The benzene and other hydrocarbons detected in the water system in the advisory area originated when plastic components of the system melted during the fires.” They further found this fires damage, “…Allowed a combination of benzene, superheated air, ash and debris to enter the main water delivery pipes at some point during and after the fire.”

As the city started replacing the plastic system with copper piping, it was forced to hand out bottled water to the community, not to mention the 250,000 gallons of clean water needed to flush the system every week.

Another example is the city of Paradise, California and the 2018 Camp Fire, which burnt 153,336 acres and torched 18,804 structures. In addition to thousands of buildings, the fire also irreparably damaged the city’s water system by melting plastic pipes, releasing benzene and other volatile organic compounds into the wider water network. According to the city, it will take 2.5 years before the water is drinkable again.

The New York Times reported nearly 30 percent of Paradise’s water samples were contaminated with benzene, a percentage that a member of the state’s Water Resources Control Board described as “jaw-dropping.” Fixing Paradise’s water system will be a financial challenge too, with estimates going as high as $300 million. As the city grapples for a solution, buildings must rely on water tanks and bottled water.

The crises in Santa Rosa and Paradise demonstrate that plastic piping is not a suitable material for preserving water quality in areas at risk of wildfire. Instead, metal piping options should be considered. As stated by Jackson Webster, an environmental engineer specializing in the effects of wildfire on water quality, “The fires in Santa Rosa caught people by surprise. Now, it has happened twice. The bells are ringing.”