Northwest US Wildfires Introduce Critical Threat to Water Quality

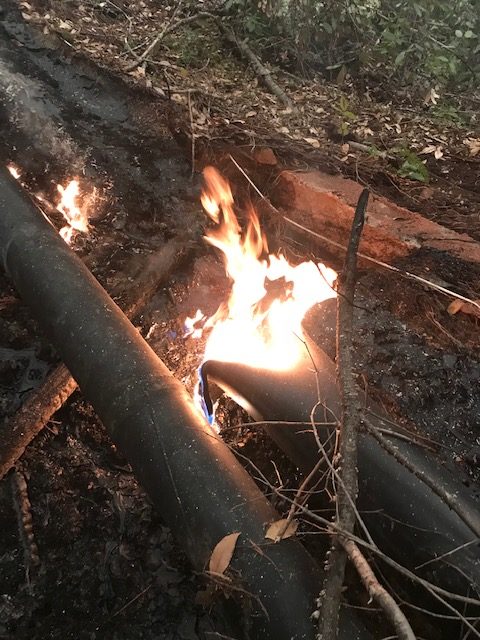

West coast wildfires have destroyed more than 6.6 million acres of land, 9,418 structures, at least 1,340 homes, and caused 37 deaths in the last three months. Some claim climate change is to blame and others site forest mitigation. No matter where you stand on this debate, wildfires are increasing at an alarming rate. According to data from the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) wildfires are burning more than twice the area than they did in the 1980s and 1990s. While the loss of land, the destruction of property, and injuries are to be expected, a new threat to public health and safety has emerged: drinking water contamination.

“Some people after the Camp Fire called me from the area,” said Andrew Whelton, an associate professor of civil engineering at Purdue University, “people who said that they took showers in potentially contaminated water and felt nauseous or lightheaded and other types of self-reported symptoms.”

The Camp Fire (2018) was the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California’s history. In addition to burning over 153 thousand acres, city officials uncovered widespread drinking water chemical contamination in water distribution networks, with volatile organic compounds such as benzene exceeding state and federal limits in public water supplies. The contamination was isolated in water networks and was not found in source water, which immediately raised suspicion on the safety of the water lines themselves rather than an external threat like contaminated air or ash. After research and investigation, piping materials, namely plastic, within these networks were pinned down as a likely cause of contamination. The destruction of water networks and widespread contamination resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars in damages and left residents without access to safe drinking waters for years.

“We now know that the combustion, the burning, the melting of various plastic components in our distribution system gave off constituents that got into the water system,” said Bennett Horenstein, Santa Rosa’s director of water. “We’re finding a very broad spectrum of chemicals that were released as the plastic burned, with benzene being the leading contaminant and the leading issue in terms of public health exposure.”

The effects of the Camp Fire and the Tubbs Fire opened doors for research and understanding surrounding post-wildfire water contamination; allowing a firm connection to be made between the plastic water infrastructure common in the hills of California and the quality of water after wildfire events. When the Western United States was rocked by historic wildfires effecting multiple states and over 6 million acres of land, concerns on water quality immediately emerged.

Water contamination stemming from the 2020 Western U.S. wildfire has already been reported in places like Santa Cruz County. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, the small town of Boulder Creek has suspected water system failures have potentially allowed harmful chemicals to enter the water supply. The flames melted several miles of pipe made of high-density polyethylene, or HDPE, that the district used to transport steam water. Following this revelation, it was determined that water was not safe to drink for residents, and that the pipe would require a replacement that will cost the city roughly 10 million dollars. In San Lorenzo, California, an area where the homes and lives of residents have been devastated by the wildfires, hundreds have also been left without access to clean drinking water after a fire burned the entirety of the city’s 7.5-mile water pipeline.

Grieving residents of Detroit, Oregon, recently returned home for the first time since the September 7 Lionshead Fire, which destroyed roughly 250 homes and businesses. With 70 percent of public buildings in Detroit burned to the ground, community members knew they were in for a long rebuilding process – however the destruction of one key facility, the area’s water treatment plant, may very well leave the town with health and safety concerns for as many as 10 years. Although too early to predict the full scope of post-disaster damages resulting from the 2020 Western US fires, it’s likely that water quality will be a concern for thousands of people. Oregon officials have already begun sampling for volatile organic compounds like benzene in drinking water.

“Experience from (California) wildfires has shown that VOCs, particularly benzene, can be found in water systems that both lost pressure and lost structure due to fire, causing plastic pipes to melt or off-gas contaminants,” said Oregon Health Authority spokesperson Jonathan Modie in an email to the Statesman Journal.

Piping, Wildfires, & Water Quality

The relationship between piping systems, wildfires, and water quality has largely been silent throughout history. Only in the past decade, have concerns been raised on how certain piping materials contaminate water supplies when melted.

“Communities need to recognize this vulnerability,” says Whelton. “Dangerous chemicals can leach from inside water systems for months after a fire.”

Whelton’s 2020 study on contamination following wildfires in Paradise and Santa Rosa sheds critical insight to the relationship between piping, wildfires, and water quality. Although benzene receives attention as the most prominent toxin found in drinking water supplies following these events, there were in fact a slew of other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that exceeded exposure limits. Whelton’s study found that dichloromethane, naphthalene, styrene, tert-butyl alcohol, toluene, and vinyl chloride were also present in excess in sampled water supplies. These chemicals are highly toxic, and pose serious threats to human health when consumed, including cancer. The research determined one consistent factor that points to the root cause of contamination, stating that plastic piping materials like polyvinyl chloride (PVC), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), and polybutylene (PB) were present in all water distribution networks affected by the fires.

The contamination can be traced back predominantly to the burning and melting of these plastic materials. When water distribution networks are constructed with these materials in a wildfire event, according to Whelton, they begin “cooking plastic underground,” thereby releasing volatile organic compounds that are inherent in their material composition into the water – as they cannot escape into the air. Volatile organic compounds such as benzene, toluene, naphthalene, and vinyl chloride are all generated as a result of the thermal degradation of plastic pipes like PVC.

The difference between prevention and enablement in wildfire-based water quality disasters lies in the material of water infrastructure. When a city or region chooses a piping material, they are making a crucially important decision in preparation for wildfire events. Water distribution networks, and all underground drinking water pipes, are composed chiefly of two major material groups: copper and plastic.

Copper pipes

Copper pipes have been used to transport drinking water for decades. Like all other pipes, copper pipes leaches into water supplies. Copper, being a natural metal, does not have a material makeup that is complex or influenced by synthetic products. The only substance that copper can leach into water is copper itself; which is generally regarded as safe to consume for the vast majority of people. Copper is a safe choice for areas vulnerable to wildfires because, when melted, it does not generate compounds that are dangerous for humans to consume. Copper is also an impermeable material, meaning that external contaminants cannot penetrate through the material and into water supplies.

Plastic pipes

Plastic pipes come in many varieties including polyvinyl chloride (PVC), high density poly ethylene (HDPE), polybutylene (PB), polyethylene (PE), and more. Plastic became a popular piping material in recent decades, being used in upwards of 50% of recent construction project in the US. Plastic pipes are composed of synthetic materials, and are manufactured using complex chemical blends, hydrocarbons, and other additives. With time, these substances leach from pipe walls into drinking water. Studies have found that the large majority of the 163 substances known to leach from plastic pipes are carcinogenic, toxic, or otherwise unregulated. Plastic is also a permeable material, and research has shown that PVC, PE, HDPE, and other pipes are at risk of permeation.

“Those benzene, toluene, xylene molecules do not penetrate copper,” says Whelton. “Plastic is more like a sponge. It has pore spaces, the atoms are not as densely compacted. The chemicals generally like to be in the plastic and not so much in the water.”

As it has been discussed, plastic pipes are high-risk in wildfire scenarios. As seen in Santa Rosa, Paradise, and other wildfire scenarios, plastic water mains can burn and melt; thereby releasing toxins like benzene into water at excessive rates. These toxins post major threats to water quality and human health. The thermal degradation of plastic pipe, and the contaminants that are flooded into drinking water as a result, make plastic pipes of all varieties unsafe in areas that are vulnerable to wildfires.

What Can be Done Going Forward?

Material selection is an essential component of preventing and reducing water contamination in vulnerable and effected areas. Considering the likelihood of an uptick in high-intensity wildfires due to climate change, the decisions made by individuals and groups who oversee water infrastructure and transportation have perhaps never been more important than now; as this issue continues to reveal itself as a high-level threat to public health and safety.

Andrew Whelton’s research team proposed that these issues could be addressed and alleviated in the following ways:

- By supporting and increasing the research that goes into testing and assessing water contamination in post-wildfire scenarios

- By employing rapid, standardized, and widespread testing to assist in determining the sources, vulnerable assets, and transportation mechanisms of contamination.

- By issuing mandatory “Do Not Use” water orders to protect public health after a wildfire in the wildland-urban interface

- By defining policy priorities before the next disaster to facilitate utility and public health response

- By significantly improving guidance to home and building owners in order to protect public health and plumbing infrastructure.

As wildfires burn hotter and longer, areas vulnerable to wildfires will need to take action to prevent drinking water contamination disasters. Policy makers, contractors, designers, specifiers, and all involved in water infrastructure and the built environment should be conscious of the repercussions associated with different building and piping materials during the selection process, and should strive to raise awareness and make changes so that water networks and communities are prepared for wildfire events.